Raising a child can be a complex and confusing. Much of this chaos and confusion is brought about by those with parental responsibility, where too much is done with or provided for the child. A child in fact just needs to feel safe and cared for. Good examples of this ‘less is more’ attitude are provided in times of war and hardship. Mary’s story encapsulates this.

Mary was born in 1940 and her family lived in a two bed-roomed house on Hutton Street, off Colwick Road in Sneinton, Nottingham. Britain was already at war with Germany and her father Eric had signed up to join the army. His brothers were already serving their country and he could not “stand by and let them fight the war for me”.

With Eric serving in the Desert Rats, it was left to Mary’s mother Rose to provide for her young family.

Sneinton was (and still is) a close community with a strong work ethic. As a young mother, Rose did her bit. She worked for the post office delivering mail. Trusted neighbours and family helped to care for Mary.

Sneinton and Colwick was the hand that fed Nottingham. The railways brought in the fuel and food; with the traders and merchants distributing it. The wholesale market was the hub for this but there was always the ‘black market’ and a country at war created opportunities for those on the home front.

Sneinton’s ‘wheeler dealers’ continued to trade

Despite being a child during the war years, Mary has some clear memories of the times. She was a happy child and it was “only the sirens made me cry”.

In 1941, the air-raid sirens were followed by bombing on a scale that Nottingham had never experienced before.

Hutton Street (a short residential street that lead to the railway line and a recycling business named Tricketts) suffered a direct hit. Mary’s home at number 22 was unscathed, but several houses across the road were destroyed.

St Christopher’s Church (directly opposite Hutton Street) was hit by an oil-filled bomb which burst through the roof before exploding and spraying its contents throughout the building; providing fuel for the subsequent fire. By the morning of the 9th of May, St Christopher’s was a smouldering roofless shell of a building.

Despite the death and destruction, life carried on. As Mary grew up, the people around her continued to provide the safety and care that all children need to thrive.

The bomb site on Hutton Street was used to build a large water tank. Water to help in putting out the fires of any subsequent bombing.

By 1944, Mary’s significant memory of the sirens and planes in the sky meant running across the road to a brick built shelter. On entering the darkness, she recalls someone asking “Who’s that?”

Another voice said “It’s little Mary”

Mary was moved along to be sat on a woman’s knee. She cannot remember whether her mother had joined them or not.

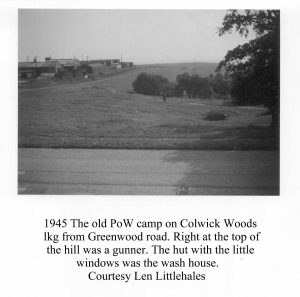

Another aspect to the war was the presence of soldiers and Mary heard talk of a Prisoner of War camp in Colwick Woods. On one occasion there was a soldier waiting at the bus stop near her home. The soldier wore an unusually big pair of boots that Mary and her friends had never seen before. Mary became nervous when one of her group said,

“ ’Ee int wonnuv ours, ‘eez wonnuh them!”

The war must have been a daily topic of conversation as everyone got on with life as best they could.

Mary waited five years before meeting her father

Only ten days after St Christopher’s Church was reduced to rubble, Mr Fred and Mrs Marion Smith walked down the central aisle to be married in the roofless ruin. The service was regarded as an indication that St Christopher’s would rise again. Shortly after the bombing a parishioner nailed a hand written sign above the door. It said ‘Resurgam‘ meaning ‘I shall rise again’. Resurgam became the post-war title of the Parish Magazine.

The residents of Hutton Street did not take it personally as other places were hit too. Mary heard that a house on Sandringham Road has shrapnel holes in the bricks.

Mary waited 5 years before her first meeting with her father and equally, he had to wait until he could resume his role in the family. Mary recalls the first meeting with this unknown man in uniform arriving at Hutton Street. She and her mother had coped but Mary had not prepared herself for his return.

“This is mine and me mam’s ‘ouse, not yours!” was her immediate reaction.

With their typical family reunited, the job of rebuilding relationships (as well as the buildings) had started.

Eric resumed his job as a mechanic for the Corporation Buses on Manvers Street.

Infants School at Sneinton Boulevard and then to The Dale Girls School on Edale Road. The family shopped within a small area, there was Clarkies Fish shop on the corner of Kingsley Road and Marriotts ‘tuck’ shop on Sneinton Boulevard where the children bought a ‘penny kayli’. Life was hard but these were good times.

Trent Lane next to Hutton Street went down to the river where there was a pleasure park run by the Courtrey family. There was a beach on the riverbank created with imported sand, a basic fair with dodgems, slot machines and swing boats. There was a rowing boat ‘ferry’ that would take people over to Trent Bridge. The park also staged dog racing. On another piece of land off Trent Lane there were open air boxing matches so that the young men could channel their energy into sport.

Children would run errands that included “tekkin a barrer to get coke for fires” This was collected from Manvers Street from land owned by Jackie Pownall. Jackie Pownall and the other Sneinton businessmen lived within the community and ‘did a lot for the kids’.

‘The Wembley Club was out of bounds to children and had a mystique about it’.

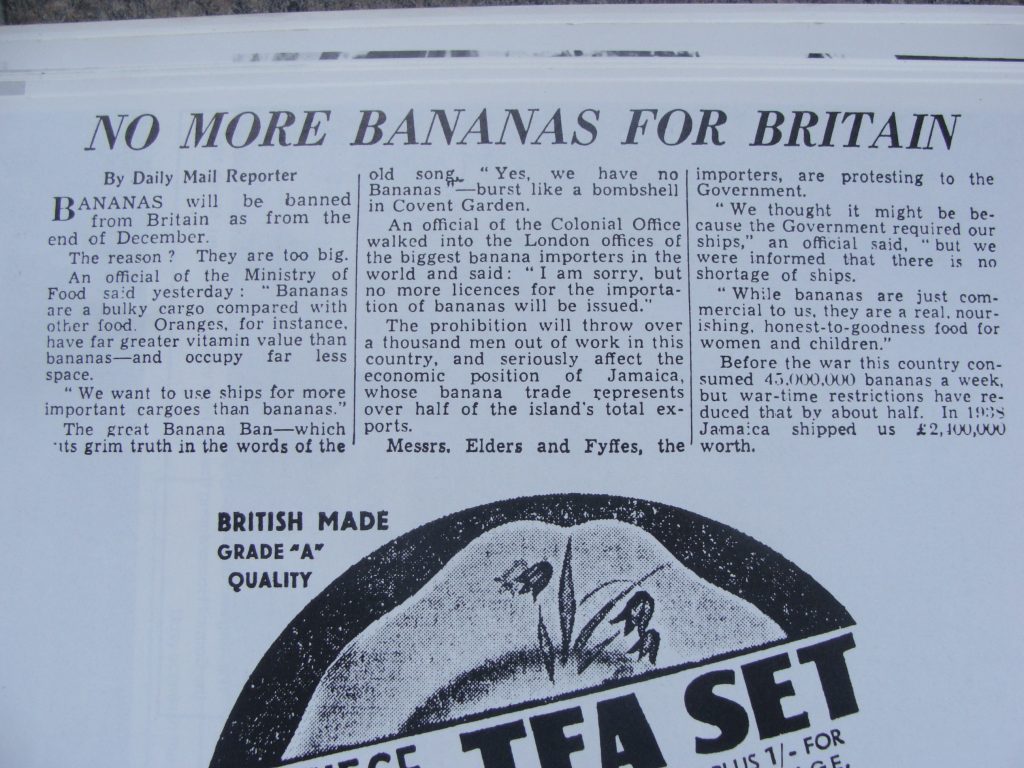

Once the bills were paid, Mary’s parents would socialise in the Dale Pub and the Wembley Club. The Wembley Club was a private members club at the junction of Sneinton Dale and Lichfield Road. It was frequented by the Sneinton traders including the ‘black marketeers’. With rationing still around and things like bananas no longer imported at pre-war levels, the opportunity to treat family to such luxuries was what made Sneinton a place that looked after its own. Rationing was all about survival. Mary does not eat bananas as she never had one as a child!

Mary can remember how important such things were. When the school heating failed, the children were still sent in order to get their bottle of milk.

The Wembley Club was out of bounds to children and had a mystique about it. The business owners and traders paid for the annual Christmas party for the children of the members.

The number 44 bus serviced Colwick Road and (at that time) also went as far as Bulwell and the outdoor swimming lido. At the time public transport was crucial to cities like Nottingham; and Mary recalls sitting on a wall waiting for her father to return from work so that she could walk home with him. As a teenager, the sight of the 44 bus caused her a different emotion. In the 1950’s Mary and her friends would use The Arena Café on Sneinton Hermitage. Previously a fishmongers, it now provided a place for the teenagers to meet and hear the first records of the emerging rock and roll scene. The possibility of her father passing on the 44 caused Mary to duck down to avoid being seen.

The late 1950’s was the time for teenage rebellion and the first generation of a defined ‘youth culture’

The place to go was on St Anns Well Road to either The Empress Picture House or the Locarno dance-hall next door. The Rock ‘n Roll nights lead to Mary meeting her husband at the age of 17. She had already been working for 2 years as an office clerk at Radio Rentals on Friar Lane in Nottingham.

Post war rebuilding for Nottingham families was an optimistic time.

As Mary says:

“These were good times, we didn’t think about the hard times, we felt safe”

I

Photographs all courtesy of Nottingham at War a Nottingham Evening Post publication from 1986

Article created with kind permission of Porchester Press